499,226. That’s how many refugees washed up on the shores of Lesbos, Greece in 2015, fleeing war, poverty, and hopelessness. It’s a number—and conflict—that’s hard to wrap your mind around. But for Zoe Wild, it wasn’t about wrapping her mind around anything; it all came down to her heart.

As she scrolled through her Facebook feed last November and saw a video of a refugee boat going down, she had a moment of pure heart and gut reaction. “I had this profound feeling in my body, like this is my family,” she says. “If it was my family I would go, and it is my family so I’m going.”

And so, a few weeks later, she ditched the relaxing Christmas vacation she’d planned and boarded a plane for Athens before traveling on to Lesbos, then ground zero for the refugee crisis. There, she worked around the clock helping boats arrive safely, greeting refugees, and buying blankets, clothes, and tents so families wouldn’t freeze to death.

As the crisis continues to unfold—including Greece now sending refugees back to Turkey—we talked to Zoe at her home in Sedona about what she learned, ways to help, and how her life course was forever changed by this decision.

Tell us about that moment when you knew you had to act.

I was hearing stories of what was going on, mainly on Facebook from people sharing the news, and then I saw the video of a boat that went down. I knew I had to do something. It was like a directive from the divine guidance that’s within each of us. So I prayed. I said, I need to do something and I have no idea what to do or how to help.

The next day I opened my computer, and the first thing I saw was my friend’s landlord was going over there, and I thought, you can just go?! I was put in touch with him and he put me in touch with a number of groups that were there. I’d planned a really relaxing Christmas vacation, but there’s a voice inside of me that I know very well. I used to be a Buddhist nun, and when I was a Buddhist nun I became well acquainted with this inner guidance. It was the same voice that told me to move to Sedona, and that told me other things in life, and it said go.

What was it like when you arrived in December?

It was going 200 miles an hour from the moment my feet hit the ground. When I got there, about 2,000 refugees were arriving a day. I didn’t sleep more than an hour a night for the first two weeks, spending all night on the beaches pulling people in, all day in the camps. It was shocking to see the complete failure of the UN, the EU, the Greek government.

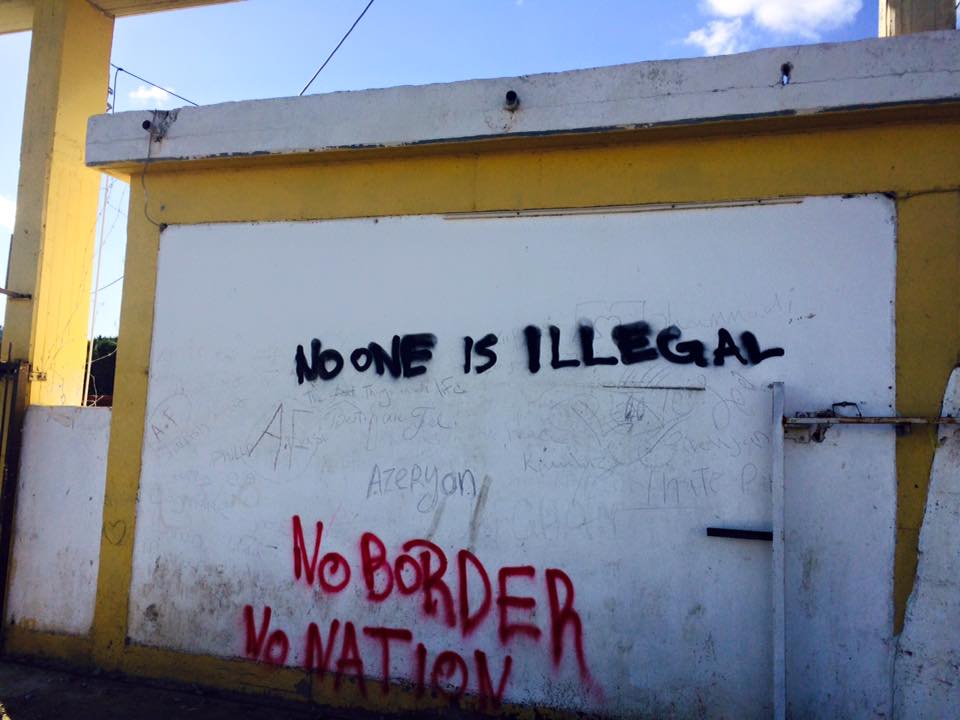

I don’t consider myself a naïve person. I was an eyewitness to the World Trade Center attacks and an eyewitness to the uprising in Burma, among other things, and this was different, to see the UN letting children die, letting people freeze to death, when here I was offering to buy heaters. It was heartbreaking and shocking. And it was totally surreal—that me, Zoe from Arizona, one person, was sometimes the only person on this stretch of beach at night, me and some woman from Sweden, making sure these boats didn’t drown. Sometimes there were a lot of volunteers and sometimes there weren’t. It was like, where’s the military? But it was illegal to help them, because they consider them illegal immigrants, even though they’re war refugees.

There are many stereotypes and fears about the refugees, especially with the terrorist attacks in Europe. What’s the reality you saw in Greece?

The reality is they are just like us. These are families who had good lives in Syria and have been in a war-torn country for five years and an oppressed regime for 30 years. We’d run just like them. They would prefer to stay. They don’t want to leave their home, friends, family, jobs. But none of those things exist anymore. When we see the bombing in Brussels or Paris and think oh that’s so terrifying, that’s what they’re experiencing from Assad and ISIS and the Russians. Every single day. Hundreds of thousands of people have died. There are mass graves, chemical warfare, a police state. The reality I experienced is that these were families, mostly children, women, elderly people, injured people, disabled people, and all they want is a safe place for their family and a chance to live their lives in peace.

You’ve shared many stories on your Facebook page, including a photo of a 2-day-old baby born on one of the boats. That blew my mind, thinking of the mother giving birth in this terrifying situation.

There were women who gave birth on the beaches too. Another baby, Fatima, would not stop crying, and so I’d take her and she’d stop. When anyone else would take her, she’d start crying, so her mom kept putting her back in my arms. How does that not break your heart open? One of the refugees told me, anyone who’s made it to Lesbos has risked their lives 12 times at least. That’s not something you do unless you’re running from something terrifying. I heard so many stories from refugees, of Assad and of ISIS, that were hard to comprehend they were so terrifying. I’m someone who works with prisoners and veterans; I’ve heard a lot. I’ve never heard stories like this. I think we need to realize it could so easily be us. That we’re just a couple natural disasters or a military coup away from being refugees ourselves …

Unfortunately, we sometimes distance ourselves from that instead of putting ourselves in the refugees’ shoes.

Especially in America, though, chances are it was your family. Unless you’re 100 percent Native American, you’re an immigrant. Most people don’t leave their home unless they’re fleeing something, even if that’s just poverty. It wasn’t till I went over there that I realized I was doing for people what others had done for my grandparents, who escaped Nazi Germany and Austria and swam ashore in Palestine and Chile. The only reason I exist is because other people had broken laws or volunteered and helped my ancestors in the way I was now helping people.

In one of your Facebook posts, you wrote, “You guys, Is it possible to fall in love this many times?” Can you tell us about a few individuals you’ve fallen in love with?

There are so many. One is this boy Zabih, he’s 15 and from Afghanistan. His parents were killed in a bomb blast. He walked to Kabul to his uncle’s house, but his uncle had a lot of kids and no money to feed them. So he and his cousin left and were smuggled across Afghanistan and Turkey over the mountains, walking and in cars, and at one point three of them were killed in a car accident, and they were crammed into a van so tightly they made him take off his jacket so he could fit. He came to the camp and spoke English really well, because at night when the other kids would sleep he’d study English. He’s in Germany now. He only wants to learn, and he’s having a really difficult time getting into school. He was so inspiring to me—so positive, intelligent, and kind—and he’s been through more than we can imagine.

There are so many. One is this boy Zabih, he’s 15 and from Afghanistan. His parents were killed in a bomb blast. He walked to Kabul to his uncle’s house, but his uncle had a lot of kids and no money to feed them. So he and his cousin left and were smuggled across Afghanistan and Turkey over the mountains, walking and in cars, and at one point three of them were killed in a car accident, and they were crammed into a van so tightly they made him take off his jacket so he could fit. He came to the camp and spoke English really well, because at night when the other kids would sleep he’d study English. He’s in Germany now. He only wants to learn, and he’s having a really difficult time getting into school. He was so inspiring to me—so positive, intelligent, and kind—and he’s been through more than we can imagine.

There were so many women about my age. It was like meeting all my sisters. They are so strong, kind, and loving. They just want the best for their children, and a lot of them have lost their husbands. They would be in tears from any help we could give, whether it was medicine or a tent for the night, and we would sit and talk about the war but also just talk about the things you talk about with people—relationships, raising kids, what they’d done in Syria. I fell in love with all of those women. And then there were some refugee men who, when I would go around at night setting up tents, would help me as a translator. They’d get so excited to help other people. They would say, I don’t want a tent, let’s find a family that needs it more.

I think it’s easy to fall in love, because you’re forced to your basic humanity; you’re in this insane situation and you’re laughing and caring about people together. I saw the best and worst of humanity every day. In the refugees I saw the best—the strength, compassion, gratitude, and generosity even when they had nothing. And same thing with the volunteers—ingenuity, creativity, selfless service.

Once you got there, did you keep extending your ticket?

I did. Over and over. I ended up staying a month or a little more and then had to come back because my own mother was dying. She passed away a month ago from cancer. I also hadn’t set up my life to leave for so long. I had a two-week ticket, I thought I’ll slip in I’ll slip out, my clients won’t even notice. Instead I was horrified and started sharing on Facebook and ended up raising $60,000 and changing my life. I quit my job and started a nonprofit, One Light Global. We’re funding a school and building an orphanage in Turkey now. I’m going there in May. We’re also helping at Idomeni, the tent city, and we help some families in Syria and Iraq.

So is the nonprofit a way to have broader impact?

I wanted to do something with a little more infrastructure and more long-term. I was connected to this school in Turkey that was started by refugees for refugee children. About 467,000 of the refugees in Istanbul are children, and of those, only about 20 percent are in school. So we’re creating this lost generation of children who are not receiving education. This is the generation that hopefully will rebuild Syria someday; they need education. My team on the ground in Turkey is mainly refugees, because I didn’t want to be the American coming in and telling them what to do. They just found seven kids yesterday who’ve never been in school, but we have to find funding for them, so that’s what we’re doing. It only costs $250 to send a kid to school for a year.

That’s an important reminder: It’s a struggle to make it to Europe, but it’s hardly a guaranteed happy ending—it’s the beginning of a long journey.

It was heartbreaking, because when people arrived in Lesbos, they had no idea what a horror show was waiting for them. They kind of thought it was the end of the journey and now you’re there to take care of them, and instead people were dying at the camps. And then waiting and waiting and dying on the way to Macedonia, or dying at the border of Macedonia, and then you get to Germany or Switzerland if you’re lucky and you’re waiting for years in camps. I know this one woman has been trying to reconnect with her husband for a year, and because of red tape they’re not letting him see her and their children. She’s 26 and losing her mind. And she’s one of the lucky ones.

Were the refugees you met willing to talk about the trauma they’d been through?

Oh my god yes, they couldn’t talk fast enough. They would tell their horror stories. I have for several years been facilitating Healing of Memories workshops through the Institute for Healing of Memories, which was started by Father Michael Lapsley of post-apartheid Africa, who had both his hands blown off in a letter bomb. He discovered this incredible power of healing through sharing our stories with groups of people that have been through similar things. By sharing traumatic stories with groups in conflict, we unite and see the humanity in each other.

How’s your heart doing through all of this?

That’s a great question, because my mother’s passing is also in there. My heart feels very big. And by that I mean it feels like it’s holding all of the extremes of the human condition—an incredible amount of love, gratitude, inspiration, connection, and joy, and an incredible amount of loss, sorrow, and brokenheartedness at the capacity of what humans can do to each other. And also a fullness of what humans can do for each other.

It feels like it’s holding the whole world. Not like I’m holding the whole world, but like the human heart has the capacity to hold the whole world inside of it. I think that’s what we need in order to move forward as humanity: the courage to hold all of it and to not just look at the suffering and be broken or to just look at the positive and ignore the suffering, but to hold all of it and move forward with wisdom and compassion.

Beautifully put. And not always easy.

Yeah, sometimes you just want someone to show up at your door with a beer and a movie. [Laughs.] I hike a lot. I go horseback riding. That’s how I deal with it. For me nature is the only thing that’s big enough to hold it.

You’ve been a Buddhist nun, a Buddhist chaplain, and a Sufi interfaith minister. Did those different threads also serve you well in this experience?

I could not have done this without my spiritual core—without my Buddhist practice and what I gleaned from two years meditating in a monastery in Burma. I saw so many people volunteers who were broken in despair. I have a strong foundation in believing that underneath, everything is happening just right. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to respond with all my might, but I respond and then let go as a result of that—usually. I try to show up, do what’s in front of me, and trust there’s a bigger picture than me.

Someone posted a quote on my wall from Lilia, who was an aboriginal elder, that really hit it on the head for me. She said: “If you’ve come to help me, you’re wasting your time. If you’ve come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us work together.” And I thought, that. That's how I feel. We’re just one family.

I imagine you’re still quite connected to the network in Greece. Any signs of hope?

Oh my gosh, it’s getting so much worse. At first everybody went to Lesbos and there was so much aid.  Then a few weeks ago the EU made this deal with Turkey to basically pay them off to send all the refugees back, and it’s a humanitarian crisis. It will be mortifying in history, like when they sent the Jews back. They forcibly removed all the refugees from the camp. It’s a disaster. I think right now the EU is really failing, and I see that it could be a simple solution: You provide safe passage and use the billion dollars you’re going to give to Turkey and create a facility in Greece that’s a safe place for them to stay and be processed, and then they get divvied equally among European nations, Canada, and the U.S. It’s not so many it would make a huge impact, and historically refugees have a positive impact on communities they move to. I think this is going to be a real dark spot in our history.

Then a few weeks ago the EU made this deal with Turkey to basically pay them off to send all the refugees back, and it’s a humanitarian crisis. It will be mortifying in history, like when they sent the Jews back. They forcibly removed all the refugees from the camp. It’s a disaster. I think right now the EU is really failing, and I see that it could be a simple solution: You provide safe passage and use the billion dollars you’re going to give to Turkey and create a facility in Greece that’s a safe place for them to stay and be processed, and then they get divvied equally among European nations, Canada, and the U.S. It’s not so many it would make a huge impact, and historically refugees have a positive impact on communities they move to. I think this is going to be a real dark spot in our history.

Any parting words for us?

You can make a difference. One person makes a huge difference, and of all that I was able to give with the help of the donors, what was reflected back to me was that what made the biggest difference was I cared; it was sharing love. I'd encourage everyone to know they can make a difference and to listen to that voice inside, and to make whatever difference they’re called to make. Don’t be shy.

Want to Get Involved? 4 Ways to Help:

- Donate to One Light Global. You can specify how you’d like your money spent (e.g., sending a child to school, helping women, emergency aid in Idomeni).

- Contact Zoe Wild about volunteering in Athens or Idomeni.

- Organize a drive for books, school supplies, or clothes for the school in Turkey.

-

Write to your political representatives and tell them you want to welcome refugees in your community.

Top photo by Mehmet Bilgin via Flickr (cc); other photos courtesy of Zoe Wild and volunteers on Lesbos