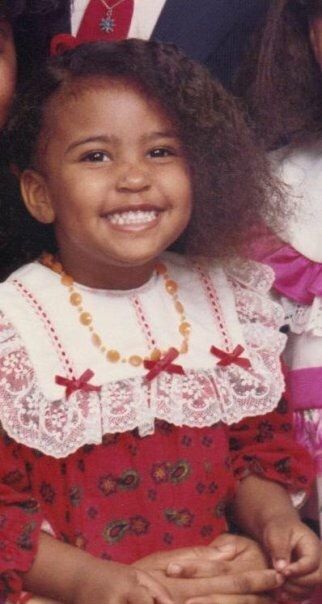

As a child, my hair poofed carelessly down my back. My Granny, a beautician, taught me early the necessity of monthly deep conditionings and the trimming of split ends to ensure long and healthy hair. The length of one’s hair was important for women and girl-child alike. Society tells us there is beauty in length, femininity in length—regardless of race. Every week I was piled high on top of pillows to give me height while at the shampoo bowl of her beauty shop, The Pink Panther. I loved most when she pressed my hair, tapping the scorching metal comb on a damp towel to sizzle before warming it through each pinned section. I loved the sweet smell of burnt hair and oil sheen mixed with the hum of chair dryers and “grown folks” talk. Nothing could keep me out of Granny’s chair, not even the imminent fate of a singed ear and head-jerk from the graze of the fiery comb. I felt my best self after a fresh shampoo and press, leaving big spiral curls bouncing all over my head. My black girl joy was enough to fill the room as the women under dryers beamed at my simple existence.

Long before Granny’s beauty shop, our ancestors combed and plaited their hair into intricate styles as way of celebration, communication, and the bonding of sisterhood over coarse coils. Hairstyling for us has always been about something more than what we do to our hair. The way in which we wear our hair has historically been an act not just of celebration and identity, but rebellion. Rebellion against white supremacy and its oppression, its rigid rules of what’s aesthetically acceptable under European beauty standards—standards that white women themselves have a hard time living up to. Standards that white people have tried to regulate and impose on us, from the workplace to the military to the school system.

While my hair story begins with a child’s glee beaming through a beauty shop, it was not always that way. What I thought about my hair shifted when I went to foster care at the age of 7. The weekly trips to Granny’s shop were replaced with boxed perms being slathered into my scalp while I sat on the floor between my foster mother’s legs. She tried to tame the volume of my hair and refused to pay to get my hair done professionally, despite my vast beauty shop knowledge and experience. She often told me how her mother was black and Native American so she had “good hair.” I did not. Over the next 10 years the super-strength relaxers acted as chemical shears. My overly processed hair grew shorter and in the opposite direction of my shoulders, just like my confidence—in the opposite direction of me. It pained me to hear my adopted family comment on how much prettier I’d be if my hair were still long.

That, mixed with me being the only little brown girl with braids in a classroom full of red, blonde, and brunette girls with flowing tresses, caused hair to become a sore spot in my life. A lot of how I viewed myself aesthetically was rooted in how different my hair was from that of my peers. Mine, even when relaxed, did not flow like the other girls’ hair, which did not require Blue Magic or Indian Hemp hair grease. It made me wonder if my hair was one of the many reasons none of the white boys wanted to date me. While they never directly called me unattractive, my male peers made it evident that the only black girls who caught their eye were the mixed girls with curly hair, freckled faces, and fairer skin.

That, mixed with me being the only little brown girl with braids in a classroom full of red, blonde, and brunette girls with flowing tresses, caused hair to become a sore spot in my life. A lot of how I viewed myself aesthetically was rooted in how different my hair was from that of my peers. Mine, even when relaxed, did not flow like the other girls’ hair, which did not require Blue Magic or Indian Hemp hair grease. It made me wonder if my hair was one of the many reasons none of the white boys wanted to date me. While they never directly called me unattractive, my male peers made it evident that the only black girls who caught their eye were the mixed girls with curly hair, freckled faces, and fairer skin.

As I grew up and into myself, I realized it was important to seek women who looked like me, whether that was by staying current on black TV shows or being taken under the wing of one of the few black moms in my small town. I sought a sameness I didn’t realize I was missing when comparing myself to my peers who looked nothing like me. Lynette was the mom of one of my black friends in high school. She stuck out in our small rural town, and it was fabulous. She was audacious and confident. She wore waist-length individual braids and a smile that felt like home. During the 12 to 24 hours it would take for her to braid my hair, Lynette gifted me with words of assurance in the beauty of who I was as a little brown girl in a predominantly white community. In those hours, we laughed over understood colloquialisms and the ignorance of the racism in our town. She told me I was beautiful, and the pop of her comb dared me to believe otherwise.

Societal norms almost destroyed the confidence I had in my hair as a young black girl. Now, as an adult, I carry the gifts of women like Lynette, my grandmother, and all the sister-friends I’ve shared community with over hair. So when I see a woman not in our cultural community profiting off of and being glorified for wearing “trendy styles” like sock buns, synthetic ponytails, and swooped edges, it bothers me. It’s about more than hair. It’s how the hair culture of women of color is used and misused. In elementary school, I was ridiculed for twisting my long braids around themselves to look like Scary Spice, but when a white girl wears Bantu knots in 2017 it’s called fashion. It feels like boxer braids are cool on white girls but not on little black girls boxing the system—literally fighting for an equal education in a school system that sends them home for having hairstyles that conflict with the student handbook’s code of conduct. Our hair is one of the many things that sets us aside and makes us unique as a people. When there are black-specific constrictions in the corporate world while the same rules don’t apply to white folks, black people are being told that our culture is only okay when it’s not on us.

It’s painful to see hairstyles that embolden me—hairstyles that black women are still fighting to be able to wear—be accepted and glorified on white women. When non-people of color wear a style and call it something different, the roots of the style are lost. The lack of acknowledgement to our culture is a disservice to why we hold that part of our culture so dear. After centuries of oppression, we are not costumes you get to put on to feel sexy or cool or current.

Today, I feel like black women are unapologetically owning their hair, their culture, and themselves despite pushback from outdated societal norms. In doing so, we as a culture are unlearning and re-educating ourselves about pride in who we are. It’s important for those outside looking in to understand that. With online applause from black-positive mantras and hashtags like #teamnatural #curlsonfleek #blackgirlmagic #melaninpoppin, we are no longer being silent when society praises our features on other faces.

Today, I feel like black women are unapologetically owning their hair, their culture, and themselves despite pushback from outdated societal norms. In doing so, we as a culture are unlearning and re-educating ourselves about pride in who we are. It’s important for those outside looking in to understand that. With online applause from black-positive mantras and hashtags like #teamnatural #curlsonfleek #blackgirlmagic #melaninpoppin, we are no longer being silent when society praises our features on other faces.

One of the times I felt most like myself was a few years ago when my hair was styled in purple thigh-length box braids. My personality entered the room before I did. The bold, shining purple danced past my hips with each step, making a statement that only black women’s hair can make. My braids challenged the stereotypes of what I was taught black girls could do with their hair. It defied what I believed I couldn’t do.