In 2004 I apologized to the Peace Corps for being raped, because I believed them when they told me it was my fault.

The messages I received during my counseling from Peace Corps have stayed with me as little reminders, embedded in my psyche. Don’t tell people you’d been drinking the night you were attacked. Don’t tell anyone in Mali (or anywhere) what happened to you, it might put you at risk. Think about what you wear before you leave the house.

This victim-blaming doesn’t exist only in the Peace Corps, of course—the social norms that foster sexual violence permeate American society, the countries Peace Corps operates in, and our world as a whole. But the Peace Corps has a choice and a responsibility in how it responds to volunteers who’ve been assaulted.

It wasn’t until seven years after the attack that I realized my experience was representative of a systemic problem at the Peace Corps. In 2011, I sat on my futon in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and cried as I listened to a group of volunteers share their sexual-assault experiences on “20/20.” Then I got mad. It was the first time I’d thought more critically about the therapy I’d received as a volunteer. Before then I’d recognized that some of the messages were unhealthy, but now I saw how widespread this culture of victim-blaming was. I dug through my journals and wrote my rape story for the first time, but I wasn’t ready to come forward yet; I still had too much shame around my attack.

Last week, as I read about the report that found nearly 1 in 5 volunteers are assaulted during their service, I felt inspired to dig around for more information. There was one ray of hope in a blog post from a volunteer who’d had a positive experience with the Peace Corps post-attack, but as I read other news, it sounded as though not much had changed since my experience. When I learned the Peace Corps recently suspended its director of the Office of Victim Advocacy, Kellie Greene, who then filed a whistleblower complaint, I realized the fundamental ways in which I felt Peace Corps failed me likely hadn’t changed.

And so, finally, it’s time to share my story.

I was raped in Bamako, Mali, when I was a 22-year-old Peace Corps volunteer. Following the attack, I called the Peace Corps emergency number in shock and was told I’d have to wait an hour and a half until the medical office opened. Peace Corps staff told me I could report the attack to police, but I would have to tell my story to a bunch of Malian men who would perceive it as being my fault as a white woman, and there would likely be no consequences for the perpetrator. A few hours after being convinced not to press charges, I changed my mind, but Peace Corps staff told me it was too late, even though we had done a rape kit and I knew the full name of my attacker, his nationality, where he lived, and his employer. Other little things seemed off, too: For example, my medical evacuation itinerary was accidentally printed to the volunteer lounge by Peace Corps staff, alighting both volunteer gossip and concern.

After getting flown to Washington, DC, I received counseling from a Peace Corps clinical social worker six days a week for about 40 days. The rules of the game quickly became clear: The decision of whether I returned to Mali was not mine to make—Peace Corps would need to decide if I was a liability first. I needed to show remorse for the risky situation I’d put myself in, and if I was still in counseling after 45 days, my contract as a volunteer would be terminated.

From the moment I landed in DC, I was set on going back to Mali to continue my work in a small village 110 kilometers from Bamako. I loved my community and felt a deep commitment to the work we were doing together, including starting a mobile banking system and creating income-generating activities with women. I was terrified the rape would be a defining moment in the direction of my life, and I felt powerless to influence my future. Instead of finding healing in the treatment sessions, it felt like I was being trained in how to accept responsibility for my “role” in being attacked.

My counselor told me the man who raped me probably didn’t know he was doing anything wrong. That culturally that’s the norm in West Africa. While the norm is horrific, I refuse to believe he didn’t know he was doing anything wrong when I was screaming, trying to escape from the locked room, and wrestling him off of me.

She asked me to explain every choice I’d made before, during, and after the attack. Every minute of that night was dissected for evidence of what I had done wrong. I spent sessions working with my counselor to brainstorm ways I could keep myself safe in the future; we replayed the night’s events and she asked me to write down each decision I should have made differently to keep myself safe.

After years of intensive work to unlearn the messages I received, I started to better understand the fundamental problems with my treatment. Peace Corps, as it currently operates, assumes the position of both employer and treatment provider in the wake of an assault, to the detriment of volunteers. Having my employer be responsible for my treatment didn’t allow me to process my experience and heal the way therapy is intended to. Instead it taught me to take responsibility for something that wasn’t mine to own, beat myself up for my “mistakes,” and be guarded and fearful over every word I shared with my counselor, knowing everything I said could potentially be used to terminate my contract. She made it clear she was assessing everything, including the way I was sitting in my chair if I happened to be wearing a shorter dress.

Every time I sent an email to anyone on staff in Mali, including the volunteer liaison who was a friend of mine, it would end up in my counselor’s inbox and we’d have to discuss it. One time I asked simply, if I did return to Mali, if there was a possibility of having either a car or another volunteer travel with me out of Bamako and back to my site, because I was worried about PTSD and being triggered. My counselor reminded me it wasn’t my place to be asking those kinds of questions because the decision wasn’t mine to make.

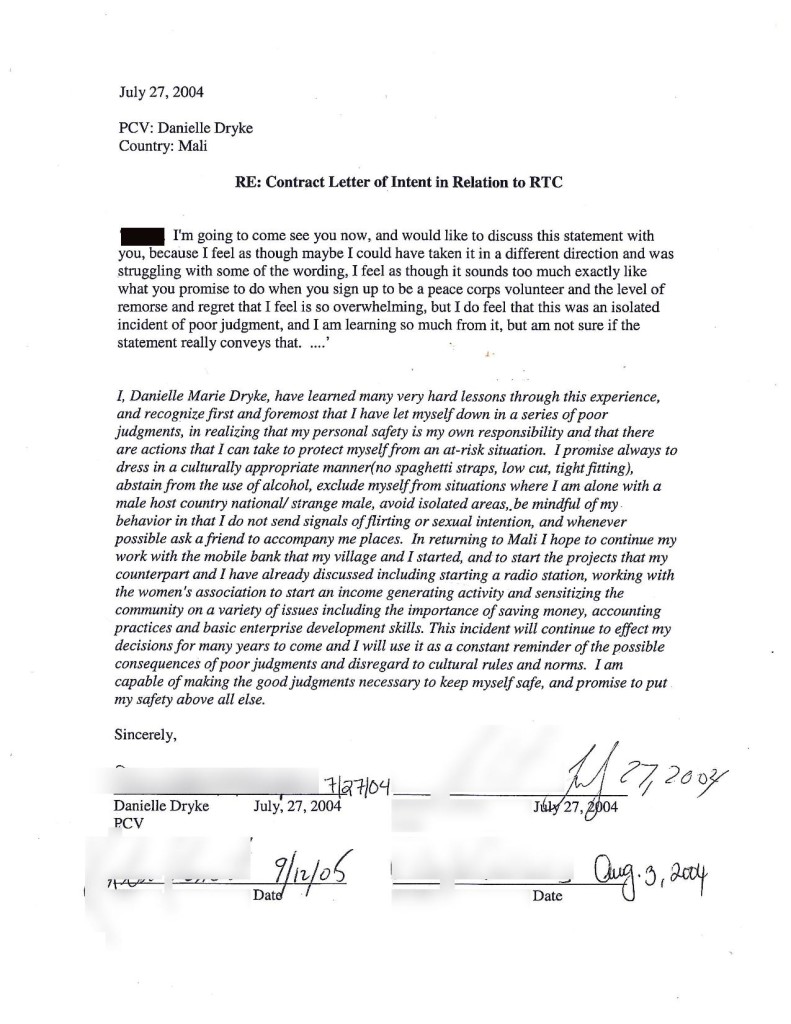

My counselor instructed me that in order to Return to Country (RTC), I needed to write and sign a letter of intent taking responsibility for my actions and sharing how I would keep myself safe in the future. I was also required to sign an agreement saying I would never consume any amount of alcohol again as a volunteer (I’d had one night of drinking in 10 months of service) or I would face immediate administrative separation.

In the letter I wrote, I knew I was telling Peace Corps what it needed to hear in order to finish my remaining 13 months of service, but I’d also deeply internalized the messages. So much so that it has taken years for me to willingly disclose to others the circumstances of my rape. I requested my medical records around the time of the 2011 legislative hearing, but this week was the first time I let anyone else read them. I'm sharing my letter below (which was signed by three Peace Corps staff responsible for responding to safety concerns), because it’s time. As you’ll see, my counselor included in the letter a portion of the email I’d sent her explaining my uncertainty about whether the letter sufficiently conveyed my “remorse and regret.”

It’s been 11 years since I was attacked, and still I’ve only told a handful of people what happened to me that night. Even re-reading the letter this week in preparation for this piece, I felt the old voices creep into my mind. Insidiously sharing with me that maybe I should just keep this to myself. Wondering how it would affect my relationships, my family, my employment. Questioning how I would be judged. I hate that that’s the reality of the world we live in, but I refuse to accept the blame for being attacked.

“Victim blaming” might as well be called “perpetrator protection.” We can all feel a little safer if we can pinpoint the reasons that someone was attacked, but it’s a destructive myth embedded in our cultural framework. It perpetuates the myth that we have control over what happens to us. And it eliminates the empathetic response that’s needed when survivors are stripped of their self-determination through the destructive choices of others.

We need to recognize that violence is endemic in our society. I believe healing it requires us to agree and publicly acknowledge that violent acts are the choice of the perpetrators. Ignoring that truth, as the Peace Corps has, fosters violence by reinforcing harmful social norms and promoting unequal power between genders by allowing alleged male perpetrators to return to service while terminating female victims.

After more than 11 years of hiding behind shame, I’m ready to shout: I did not make the decision to be raped. It does not matter what the circumstances were, it does not matter what I was wearing, if I’d been drinking, where I was, or how I behaved. I did not ask to be raped. No one has ever asked to be raped.

I was victimized by the violent act of another human being. I was revictimized by the Peace Corps. And it’s time for change. There needs to be a separation of the mental health treatment of volunteers from the supervisory role the Peace Corps has as an employer. Liability assessment has no place in processing a traumatic event. And treatment should not be used as a means to inflict shame and perpetuate self-blaming mentalities that victims so often already experience. It needs to be a means to healing, to ensure one incident does not negatively affect the course of a life in perpetuity.

I was victimized by the violent act of another human being. I was revictimized by the Peace Corps. And it’s time for change. There needs to be a separation of the mental health treatment of volunteers from the supervisory role the Peace Corps has as an employer. Liability assessment has no place in processing a traumatic event. And treatment should not be used as a means to inflict shame and perpetuate self-blaming mentalities that victims so often already experience. It needs to be a means to healing, to ensure one incident does not negatively affect the course of a life in perpetuity.

Now, this minute, we must approach sexual assault victims with open arms, while condemning the acts of the perpetrators. The shame, guilt, and self-hatred I learned as part of my treatment from the Peace Corps is preventable, through care that puts the survivor first and allows individuals the space, freedom of expression, and compassion necessary to heal.

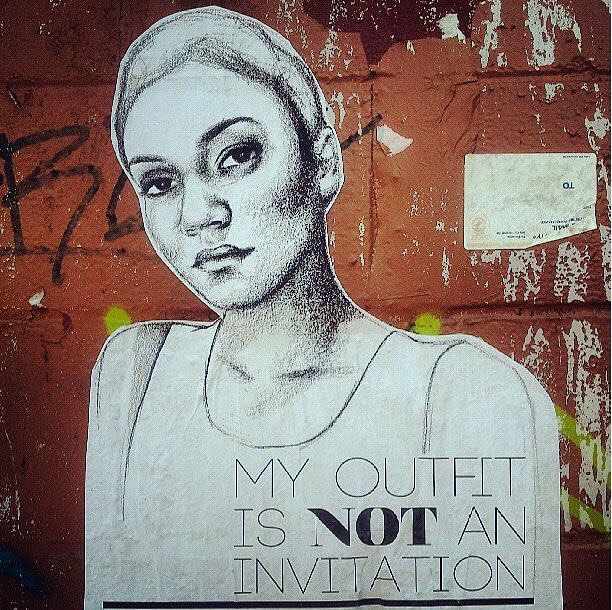

Photos: “My Outfit Is Not an Invitation” by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh; “Stop Blaming Victims” by Wolfram Burner (cc)