There it was, my grandmother’s 1950s Singer Featherweight sewing machine, glaring at me. Its recently refurbished black frame shone with grease from the repairman’s rags. I wanted to sew, but at the same time, I really didn’t. I had put off fixing the machine for years. And now that the machine was usable, I kept asking myself one thing: Is it OK for me, a modern 20-something woman, to sew?

After moving to Washington D.C. five years ago, I became obsessed with domesticity. I was working in a specialty coffee shop, and it seemed like all of my new friends were baking or canning vegetables or sewing. These millennials would fall asleep reading cookbooks, bring their knitting needles to social gatherings, or share salted caramel brownies they had made in their spare time. Being domestic was suddenly cool. I followed suit, and most weekends I found myself baking cherry hand pies or loaves of bread for my three roommates (they didn’t complain). I used my fix-it skills to organize our row house, like salvaging an old board from the back yard to turn into a bookshelf. My mom drove my grandmother’s Singer from Indiana out to D.C. so I could start sewing again for the first time since high school technical theater class. I remember weekends in that row house fondly—the kitchen was full of light and my heart was at ease.

However, over time, I began to see a darker side to this trend too. I began to notice how much pressure we were putting on each other to reject the easy way and make things from scratch. Like the time I promised colleagues I would make a birthday cake for a potluck but then got sick several days beforehand. The afternoon of the gathering, I felt well enough to attend but not fully recovered. Still, I decided I had to bring a homemade cake. In my mind, showing up with a store-bought dessert would be humiliating. The recipe was supposed to be easy. I had all the ingredients I needed. I would bake if it killed me.

I flung my ragged body around the kitchen—in hindsight, it wasn’t the most sanitary choice—and spent almost two hours making a two-layered chocolate cake. Except, rather than coming out fluffy, the layers looked more like deflated footballs than anything appetizing. I cried in the middle of the kitchen because I felt so sick, and because I couldn’t believe I had put myself through that. Like the worst contestants on “The Great British Bake Off,” I became so frustrated that I threw the cake in the trash. I went to the grocery store and bought an oversized, dry pound cake that was perfectly fine. Everyone at the party understood. I didn’t mention that I had wasted two hours baking a different cake. But that afternoon felt like a turning point. Why on earth did I put myself through that? What had convinced me that the cake had to be homemade?

Those thoughts wouldn’t go away as I scrolled through cooking blogs like The Kitchn or design sites like Apartment Therapy. Beautiful pictures of ambitious meals, sparkling apartments, and hands-on DIY projects started to feel pressurized. My anxiety spiked every time I looked at them. I had assumed that, in order to be a “real” woman, I had to do these things. But I started questioning this idea. Did I need to spend my weekends re-staining an antique dresser I found at a vintage store? Or, rather than use my hard-earned money to buy a $5 loaf of sourdough from Le Pain Quotidien, should I measure, mix, and knead my way to the staff of life? Was I willingly re-entering the same homemaker role that my grandmother had inhabited and that women had fought so hard to escape? Suddenly, I decided if that was what it meant to be a woman, I didn’t want to be one.

After that, I completely rejected domesticity. I scoffed at it. I began to feel pity for my female friends when they would bring fresh scones to work. I would think, “That poor girl, she could have spent that time pursuing career ambitions.” I wanted to use my time toward something I considered more productive. I hoped to read, to write, and to follow my true passions. I planned to start a side hustle. I wanted to go for long walks. I would do all the things that those other women—the ones I had labeled homebound—couldn’t do. Maybe if I avoided oppressive activities, I would no longer feel suppressed.

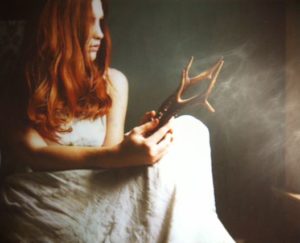

But then I noticed my grandmother’s sewing machine, tucked away under a desk. Did I think my grandmother was oppressed? She had been the epitome of a 1950s housewife. She kept an immaculate house, always dressed to the nines, and sewed clothing for her family of five on this same machine. But was she happy? I never got a chance to ask before she died. In my contemporary eyes, her lack of opportunity outside the home was a form of oppression, even if she had found parts of it  fulfilling. But could I compare her to my 28-year-old self with a full-time career and a soon-to-be graduate degree? Was it the same for me to sew as it was for her? Maybe my new thinking had become too rigid. I did not face the same expectations as my grandmother did. Back in her day, women were expected to stitch clothing for their entire family. Sewing, for me, could be a practical hobby. It could also, in theory, be fun.

fulfilling. But could I compare her to my 28-year-old self with a full-time career and a soon-to-be graduate degree? Was it the same for me to sew as it was for her? Maybe my new thinking had become too rigid. I did not face the same expectations as my grandmother did. Back in her day, women were expected to stitch clothing for their entire family. Sewing, for me, could be a practical hobby. It could also, in theory, be fun.

Then I learned from my mom that, for my grandmother, sewing seemed to be an escape. My grandmother had a dedicated sewing room where she would spend hours, often sewing clothes for herself. My mom said she seemed to enjoy it. I realized I was being too judgmental, both of my grandmother and of other modern women who chose to pursue domesticity. What of my fellow women who were stay-at-home moms? The last thing I wanted was to criticize them for their choices. Sure, baking was a gendered hobby that my mom pushed on me and not my brother when I was growing up. But it was also a skill, and one I knew damned well. And it often helped me to relax. Working with my hands had the power to ease my anxiety. To produce something tangible like a cake or a loaf of bread, something you could squeeze and taste and cut with a knife, was a reminder of what else was possible. If I could do this, maybe I could write that book. Maybe I could learn to fix a car or to play drums in a blues band. And sometimes the hobby was just plain fun.

The feminist in me struggled with what step to take next. I hesitated to re-ignite my do-it-yourself attitude because its pull was eerily strong. Even just peeking at design blogs sucked me into what felt like a DIY black hole. This void tried to convince me I should change. After reading about “5 Things Impeccably Organized People Do on Sundays,” I grew ashamed of how disorganized my life suddenly seemed. “The 7 Most Successful Ways to Make a Small Space Seem Less Claustrophobic” made me worry my apartment felt too cramped. My life did not feel good enough. I had to snap myself out of it before I got sucked back in. I re-convinced myself that I didn’t need to change to meet such impossible standards.

There had to be a compromise. I should be able to sew and bake and still be a feminist. After all, what is feminism about if not the pursuit of the choice to do, act, dress, and say whatever we want? I did, however, need to limit time spent on design and cooking websites. Their media kits show that women make up a large majority of the readership for these sites—and millions of us are reading them every month. I would need to be mindful of the power these websites hold over women. Unfortunately, too many women buy into the idea that they need to change in order to measure up. But I was over that idea. I would no longer allow myself to scroll through those websites when I was bored or anxious, filling my brain with unobtainable desires. When I did look at them, it needed to be a conscious decision. After all, I wasn’t going to catch my boyfriend scrolling through Apartment Therapy searching for a better way to organize our foyer, so I shouldn’t feel pressured to organize our foyer either.

In the end, I sat down at my grandmother’s machine and sewed. And it was delightful. I felt accomplished and capable and even a little bit badass. The next day, I started planning that side hustle. The day after that, I went to work. I finally understood that being a real woman meant being complex. And I was all for that.